Jensen Huang and Lisa Su have a lot in common.

The chief executives of Nvidia (NVDA) and AMD (AMD) aren’t just two of the most powerful people in the global AI chip industry, they’re also family.

The connection was first acknowledged by Su in 2020, and more recently, has been fleshed out in detail by Jean Wu, a Taiwanese genealogist.

The two didn’t grow up together, which may make it easier considering they now compete against each other atop one of the world’s most closely-watched sectors.

Theirs is a shared family history with roots in Taiwan, an island increasingly caught between the United States and China, as the two nations battle for supremacy in high tech.

According to Wu, a former financial journalist who now focuses on researching corporate families, Huang is Su’s “biao jiu,” in Mandarin Chinese. In Western terms, they are first cousins once removed, which refers to cousins separated by a generation, she told CNN.

To be exact, Su is Huang’s uncle’s granddaughter, said Wu, who described identifying their relationship by researching public records, newspaper clippings and yearbooks, as well as interviewing a close family member of Huang’s.

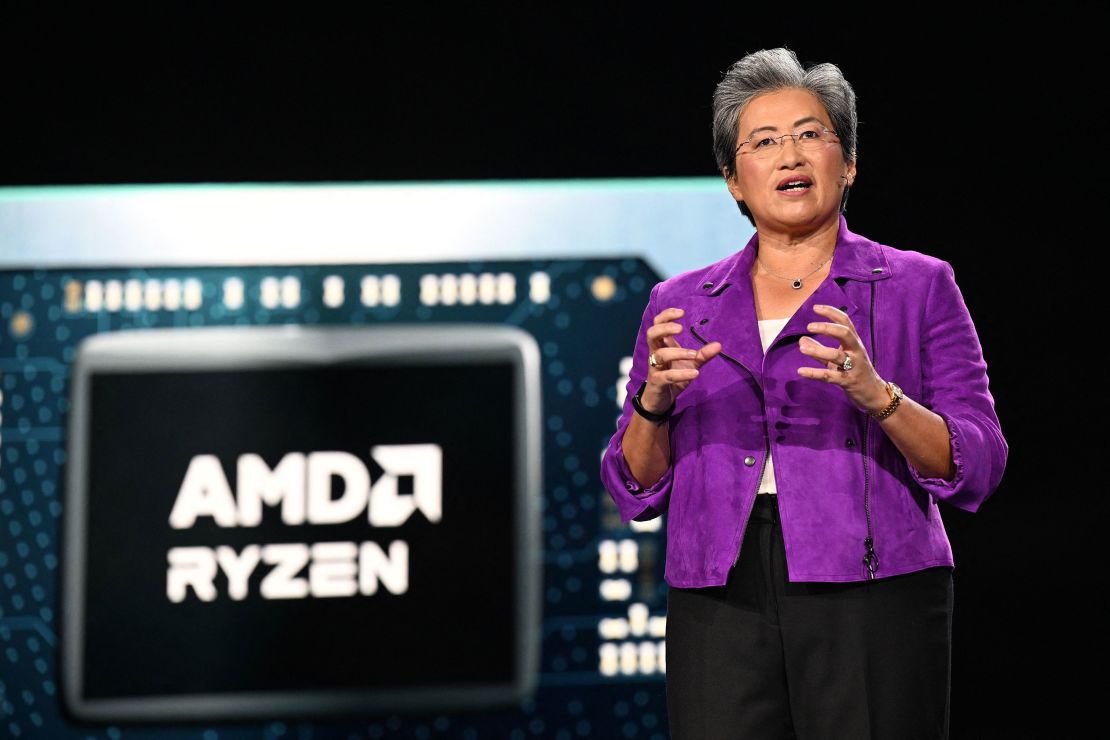

“We are distant relatives,” Su said with a smile, when asked at a Consumer Technology Association (CTA) event in 2020.

An Nvidia spokesperson also confirmed that Huang was related to Su as a distant cousin through his mother’s side of the family. Huang declined to comment for this story, while Su did not respond to a request for comment.

The link has become a point of fascination for industry watchers.

In Taiwan, where Su and Huang were born six years apart and now enjoy rockstar status, the topic has been featured on local news broadcasts. Online, users of Reddit and other forums have buzzed over the coincidence, while sketches of purported family trees have circulated on social media.

“I was really surprised,” Wu said of her discovery. “I think people in Taiwan are happy about it because the world finally sees Taiwan.”

Christopher Miller, author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology,” said he was initially astonished, too.

“But in other ways, it’s not surprising to find two people of Taiwanese descent at the absolute center of the chip industry,” he told CNN. “Because although Taiwan is a long way from Silicon Valley, in fact, there’s really no two parts of the world that are more closely networked in terms of family ties, in terms of business ties, in terms of educational ties.”

Taiwan has a long tradition of producing world-leading hardware that has propped up its economy, noted Edith Yeung, general partner at Race Capital, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm.

She credited companies such as chipmaker TSMC (TSM) and electronics manufacturers ASUS, Acer and Foxconn, as leading the way, encouraging many young people to aspire to work as tech engineers.

Miller echoed that view. “For almost half a century now, Taiwan’s economy has been centered on electronics production, chip assembly, chip manufacturing, chip design, everything semiconductors. And if you look at Taiwan’s economy today, semiconductors are the largest export,” he said.

“That means when young people are entering university, when they think about potential career paths, semiconductors are one of the most popular choices.”

Su and Huang were no exception, even as they were mostly raised abroad.

According to Nvidia, Huang was born in 1963 in Taipei before moving to the southern city of Tainan. His family later relocated to Thailand for his father’s job at an oil refinery.

When Huang was nine, political unrest in the Southeast Asian country led his parents to send him and his brother to live briefly with relatives in Washington state, who then sent the siblings to boarding school in Kentucky.

Meanwhile, Su was born in Tainan in 1969. She headed to the United States earlier, immigrating to New York City at the age of 3.

Though the two grew up far away from one another, they went on to similar paths as adults.

They picked the same field of study — electrical engineering — with Su studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Huang attending Oregon State University and Stanford University.

Later, as they landed in the fast-moving world of semiconductors, they worked at different companies, but did share one employer.

Prior to starting Nvidia in 1993, Huang worked at AMD as a microprocessor designer. Su, of course, joined AMD too, nearly two decades later, as senior vice president and was ultimately credited with turning around the company.

Now, both executives are based in Santa Clara, California, with their respective headquarters just a 5-minute drive apart.

Their companies sell hardware and software to the world’s leading tech companies, in an industry poised to reach $1 trillion in value by 2030, according to McKinsey. In its most recent annual report, AMD named Nvidia as a top competitor in two of its four main lines of business: gaming and data centers.

The firms were once best known by gamers for selling GPUs — graphic processing units — that display visuals in video games, helping them come to life. While the two still compete in the space, their GPUs are now also being used to power generative AI, the technology that underpins newly popular systems such as ChatGPT.

Nvidia’s H100 GPUs, for instance, have been used by OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT, to train its language model, according to the chipmaker. Those components have been compared to AMD’s recently launched MI300X, which it bills as “the world’s most advanced accelerator for generative AI.”

AMD said Tuesday while reporting earnings that it expects GPUs to bring in more than $2 billion in revenue in 2024, and that the MI300 series was forecast to become “the fastest product to ramp to $1 billion in sales in AMD history.” The robust projections sent AMD’s stock up nearly 10% the next day.

The two also compete in selling gear for data centers, the physical facilities used to store troves of electronic information. They rely on chips such as central processing units (CPUs), which help computers run operating systems and programs smoothly, and data processing units (DPUs), which free up space on computers so users can perform multiple tasks at a time. AMD sells both components to businesses, as does Nvidia.

In recent years, the companies have gained more mainstream recognition for providing cutting-edge technology that promises to reshape society. The processors they make are increasingly being used to help run electric cars, in addition to AI systems, bolstering a reach that had already encompassed virtually everything from PCs to PlayStations.

“I would say anyone who logs on the internet is likely touching not just one, but dozens and hundreds of Nvidia and AMD chips,” said Miller.

“Most people never think about AMD or Nvidia because they never see the chips that these companies produce. But in fact, in your day-to-day life, you likely rely on both Nvidia and AMD.”

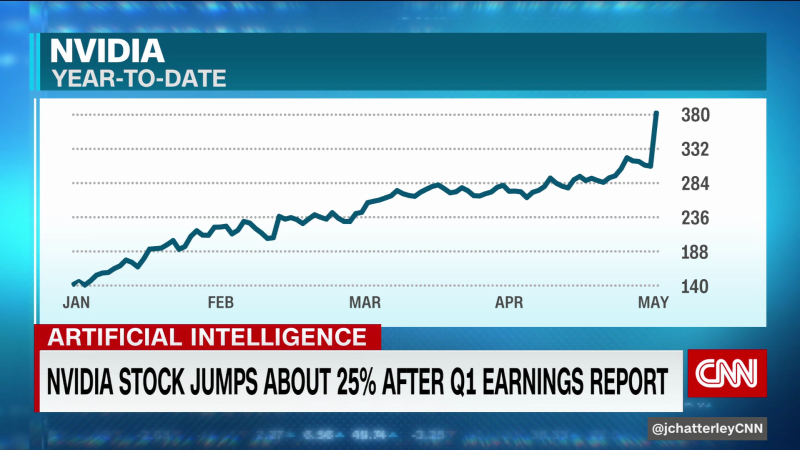

The AI boom in particular has supercharged shares of Nvidia, which is seen at the forefront of the tech required to train artificial intelligence. As a result, Nvidia’s stock has enjoyed a massive rally, climbing 208% so far this year.

AMD’s shares have also popped 73% to date in 2023, though the company is much smaller than Nvidia, Miller noted.

Meanwhile, Su has emerged as one of America’s highest paid executives, ranking as the best paid female CEO in the S&P 500 last year. She topped the list for both male and female CEOs of companies in the index in 2019, according to joint reviews by executive compensation analysis firm Equilar and the Associated Press.

Both chipmakers, however, may see their luck change as geopolitical tension continues to flare. Last week, Nvidia said in a regulatory filing that US export controls to China affecting some of its advanced AI chips had come into effect “immediately,” weeks earlier than scheduled.

The company said it did not expect “a near-term meaningful impact on its financial results,” though it has pointed to a potential “permanent loss of opportunities” over such restrictions in the long run.

AMD also said in August it would comply with US curbs, while looking to develop products specifically for China.

Such concerns would likely far outweigh any awkward family dynamic.

Asked about her relationship to Huang by the CTA in 2020, Su said “I think Nvidia’s a great company.”

“There’s no question [that] the technology capability that they have demonstrated over the last decade has led the industry to some of the key areas in AI,” she added.

“It is a competitive world, so there’s no question that we compete hard. But it’s also a world where you also have to partner with your competitors from time to time.”

Read the full article here